Q-talk 92 - FUN WITH FOAM - X-40 Part 2

- Details

- Category: Q-Talk Articles

- Published: Wednesday, 23 December 2009 16:24

- Written by Jim Masal

- Hits: 3118

FUN WITH FOAM: X-40 Part 2

Jim Masal Carrollton, TX

A typical cowling produced in volume is made by laying up glass into a female mold. The first layer of glass down will be on the outside of the cowling. Usually a layer of epoxy, called gel-coat, is sprayed into the mold before the first layer of glass is applied. Gel-coat is a viscous epoxy that often has a coloring agent added to give the newly created part a smooth and finished look when it is pulled from the mold. The labor required to finish the "show side" of the mold is saved, but a female mold is nevertheless labor intensive. It is necessary to make the plug (a part representing the desired finished product), contour it to perfection, apply a mold release agent, gel-coat it, and then apply a thick layer of glass mat, etc., often with embedded lumber to make a thick, stiff mold. Plugs are often shot with chopper guns that rapidly spew out short strands of fiberglass impregnated with polyester resin. A choppergun can quickly build up a mold to any desired thickness.

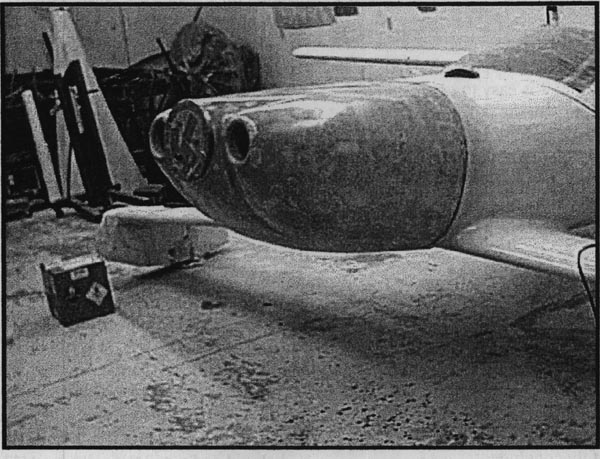

In a one-off method, such as this one, we are building a cowling right off of the plug as a male or outside mold. The plug, or male mold, will be sacrificed because it is built with less durable materials.

It is a good idea to determine the layup schedule of a similar part. This aircraft had an original Q2 cowling. By cutting off a piece of cowling and burning it over an open flame (stove or torch), the epoxy is removed and it is possible to peel back and count the layers of glass. In the case of the original Q2 cowl, there was found to be a thin layer of glass mat sandwiched between woven fiberglass. Glass mat is used in production cowls to add thickness without the multiple layers of woven glass that would increase labor costs. Glass mat, however, can soak up a lot of epoxy adding unnecessary weight unless it is vacuum bagged.

In the foam stage, we got the cowling shape very close to the desirable end result. Next, it was time to protect the foam and do any detail finishing of the shape. To do this we chose a pre-mixed drywall taping and bedding mud from Home Depot. This compound was squeegeed over the foam in successive thin layers with attention paid to filling local low spots. It dries quickly so that work can proceed without undue delay. At this stage, repeated light sanding and application of the "plaster" was done until we were satisfied that our plug was contoured very smoothly. At this point, it is possible to spray the plaster with shellac or something to seal the pores but it probably isn'tnecessary.

The plug must be coated with some sort of release agent to allow a cured glass la-yup to be pulled away from it. There are all sorts of ways to do this: the plug can be waxed or even covered with a smoothed layer of Sa-ran wrap. But by far, the most "trick" way to do it is to spray on PVA - polyvinyl alcohol. PVA is very watery and can be sprayed in a fine mist even by a cheap airbrush. When dried, it forms a continuous layer of exceedingly fine plastic film over the part. Epoxy will not stick to it. It can be peeled away like an onionskin but it is water-soluble so it is easily sponged off. It is not delicate to deal with and using reasonable care, I have pulled 5 parts off of a rotating beacon fairing mold I made without disturbing the originalPVA film.

Showtime! The plug was checked one last time to see that it had a uniform coating of release agent. Areas adjacent to the layup were masked or coated with release agent. This was a long tedious layup. Once begun, it could not be stopped midstream. I packed a lunch.

I have no secrets to doing this outside layup. This cowling had compound curves like crazy so the glass was cut on the bias in large pieces. Sticking the first layer down was the hardest and there was no way to avoid overlaps at some of the strangest places. You just take what you get. The cured part gets sand and fill on the outside anyway so the overlaps are treated at that time.

We laid up 3 layers of 8.8-oz. cloth. Along the sides, where a split line would be cut, we laid up extra tapes to provide thickness for riveting a hinge. Ditto around the perimeter at the firewall where fasteners would attach the cowl to the firewall flange. Extra glass was applied around the intakes and at the spinner opening. We didn't do it but thought was given to wrapping the whole thing in a final layer of 3 oz. fine weave cloth to soak up any epoxy rich areas and to give the finished surface a finer weave requiring less micro fill. After 5 hours, it was time for a beer.

The cowling cured for a day and a half. Next, a split line was marked on the cowl to delineate the upper and lower halves. A Dremel tool with a fiberglass cutoff wheel splits the cowl with only a narrow gap... but you can't let shaky Jake make the cut if you want to avoid a scalloped edge. By starting at the firewall and the split line, gentle prying will slowly separate the glass from the plug. Patience and care may save the plug for future use. In any case, once the cowl is removed the plug must be pulled off of the wrapped engine. We deepened the upper/lower split line cuts and were able to remove the plug in two relatively undamaged halves.

(Just speculating here, but we believe it might be possible to X-40 foam the outside of the plug and pull off a female [inside] mold done in foam.)

You can order a printed copy of Q-talk #92 by using the Q-talk Back Issue Order Page.