Homebuilt Aircraft - June 1984

- Details

- Category: Magazine Articles

- Published: Sunday, 03 May 2009 01:00

- Written by Don Dwiggins

- Hits: 21033

TURBO TESTBED

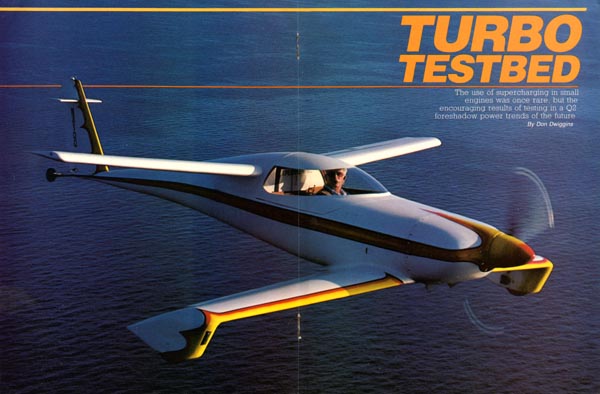

The use of supercharging in small engines was once rare, but the encouraging results of testing in a Q2 foreshadow power trends of the future.

By Don Dwiggins

|

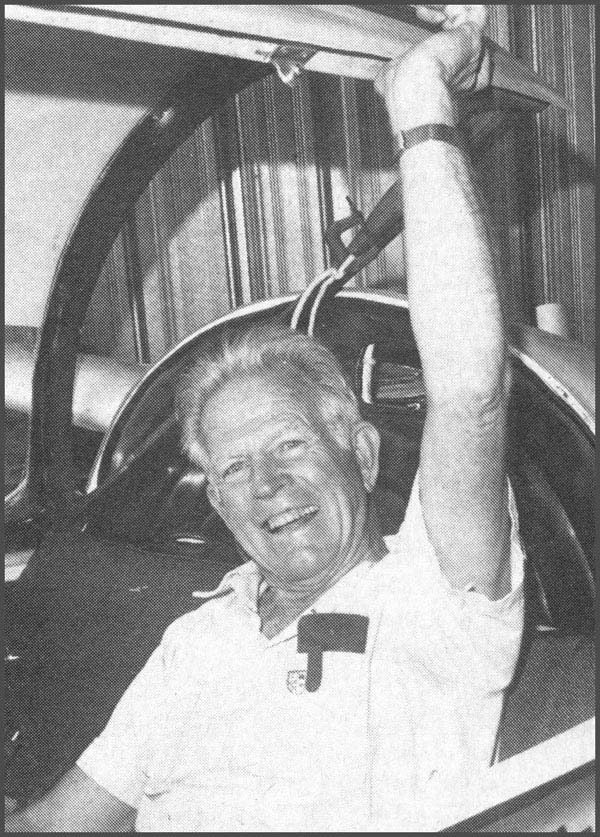

What’s all this jazz about turbo charging small engines for homebuilt aircraft? To find out, we spoke to Eric Shilling, an old China hand who once flew for Claire Chennault, and, after some 27,000 hours, may be considered knowledgeable about things aeronautic.

We also talked with Joe Horvath, head of Revmaster Aviation, makers of the R2100D-T VW-type engine in Shilling’s sleek little Q2, the prototype Turbo 75 power plant that is amazing everyone on the West Coast.

The answers we got are nothing short of exciting — a whole new way of flying higher, faster and farther in Q2s that will also work wonders for similar homebuilt types.

|

In the past it was generally assumed that aircraft using smaller horsepower engines did not require supercharging simply because they normally operate at lower altitudes. Traditionally, it was also felt that because superchargers increase the weight and cost of an engine, they were of no particular benefit to engines of less than 200 hp.

Basically, supercharging increases an engine’s power output by compressing more fuel/air mixture into the cylinders than would be induced by normally aspirated atmospheric pressure alone, thereby creating greater burning pressures. But to take full advantage of super charging, the engine must be matched with an appropriate constant-speed (CIS) propeller, a further expense.

To meet this challenge, Revmaster put together an experimental package deal, using Shilling’s Q2 as a test bed, and the results are sufficiently exhilarating that the “Turbo 75” Revmaster 2100D-T (for Dual ignition, Turbocharged) will soon be marketed.

The “package deal” includes three elements that will fall into a rough price range of $4,800 for the basic engine, $1500 for a Maloof/Revmaster CIS propeller system, and $300 for a governor/tachometer, totaling around $6,500.

(Without the computerized governor, the propeller functions in a two-position mode using a simple toggle switch.)

|

| Eric Shilling.. |

Advantages exist not only at altitude — at lower flight levels, sea level to approximately 5000 feet MSL, smoother and more efficient power delivery is quickly apparent. But where a normally aspirated engine loses horsepower with increasing density altitude, turbo charging overcomes that problem, up to what is called a critical altitude, where it will no longer produce 100 percent of sea level power.

Thus, whereas the Continental 0-200 of 100 horses at sea level delivers only 75 hp at 7500 feet MSL, the turbo-charged R2100D-T of 75 horses at sea level maintains that same power output at 7500 feet MSL.

“That is,” says Horvath, only if you are using a constant-speed-propeller. A fixed-pitch propeller cannot take advantage of turbocharging at altitude simply because the air is thinner, which enables the propeller to over speed. When that happens, to protect your engine you must throttle back, and so defeat what you’ve gained in extra power.”

|

|

Vmax in Shilling’s Turbo 75 Q2 at 3000 feet MSL |

Incidentally, different engines have their own idiosyncratic differences, and recently Shilling found he was getting sea-level power at 11,500 feet MSL, flying with 36 inches of manifold pressure and 3200 rpm (full power). This translated into a Vmax of 178 mph AS, or 220 mph true airspeed at 14 degrees COAT.

To understand more about Shilling’s remarkable Turbo 75 Q2, you need to know more about the man. He flew with Chennault’s Flying Tiger outfit in 1941 to 1942, around Rangoon. Most of his 25 missions against the Japanese were photo-recon flights, although he did score one kill.

After the war Shilling flew C-46s and C-47s with China National Airways Corp.

and China Air Transport, then DC-7s for Swissair, before retiring.

|

|

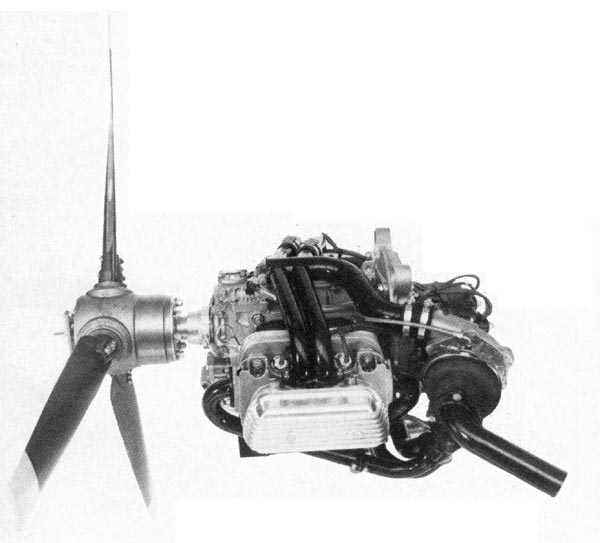

Three-bladed constant-speed prop on Revmaster 2100 D- T; |

At 67, Shilling’s 27,000 flying hours total an amazing 1125 days, or more than three years in the left seat, and now, in the homebuilt arena, he’s still going strong. His first homebuilt was a Cassutt racer, which he raced at Reno in 1969, finishing in fourth place, which was not bad for starters. Next he built a Sonerai II so he could take his wife and kids flying in a similar type.

“Then when I joined Revmaster two years ago,” he says, “I decided to build me a Q2, largely because it came the closest to advertised performance claims.”

His Q2 made its maiden flight in March 1983, behind a normally aspirated Revmaster with a wooden prop; then he switched to a Maloof/Revmaster propeller and flew in the Cafe 400 at Santa Rosa. “I had no flight-test time on the new prop and cowling, so I didn’t do too well,” he admits.

|

|

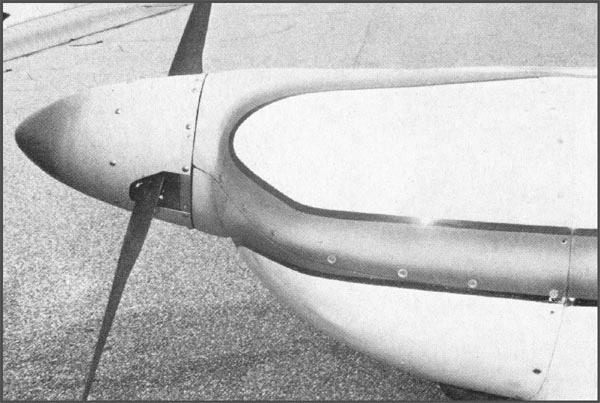

Eric Shilling’s Turbo-75 Q2 engine cowling off, side-hinged canopy open. |

At this point Horvath already was experimenting with the turbocharged engine on a KR-2; then, in July 1983, Shilling made his first flight with it under a new, longer cowl in his Q2.

Initial flight tests with the Turbo 75 were revealing. At 630 pounds empty and 850 pounds gross weight, he averaged 1000 fpm to 12,000 feet MSL, where he hit a Vmax of 208 mph AS on 75 percent power (24 inches, 3000 rpm). He was then using a two-position Maloof propeller, without the CIS governor.

|

|

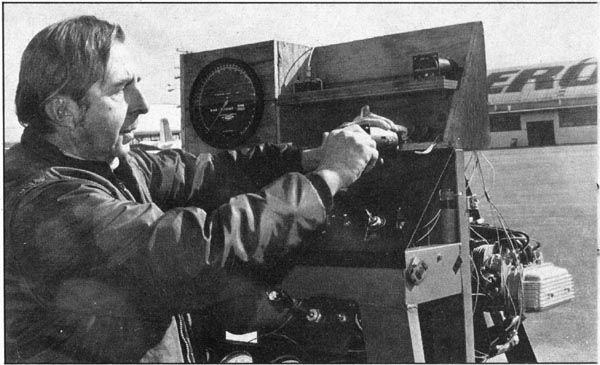

Revmaster’s Joe Horvath runs Dynomometer test on P-2100 D-T engine. |

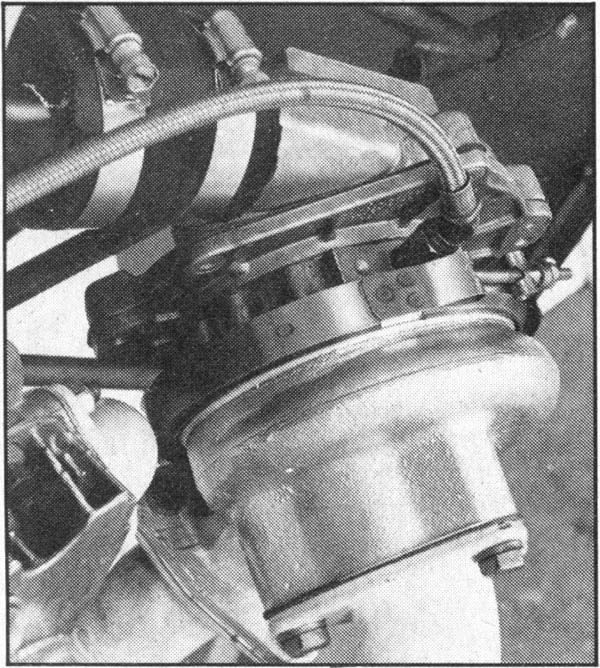

Shilling installed Rajay 300 series turbo-supercharger, now manufactured by Roto-Masta, at the front end of his engine, which required an extended cowling and a recessed area in the firewall in order to take the starter/magneto accessories. The entire power train totalled only 217 pounds. Amazingly, Shilling found he could get 90 hp, briefly, in an emergency.

“Not all of the advantages of a ‘blown’ engine are derived at altitude,” he points out. “The turbocharger is driven by exhaust gases, and the fuel/air mixture goes through the unit, so you get what is called a ‘wet’ turbo, with the impeller helping to mix the fuel and air more completely. The result is that each cylinder gets an even mixture, and I can lean to peak EGT rather than to the leanest cylinder as in a normally aspirated engine - there’s just no leanest cylinder.”

Normally aspirated, his engine delivers 65 horses, yet turbocharged it puts out 75 plus hp, so he likes to rate it at an honest 80 hp, but still calls it a Turbo 75.

|

The Revmaster R21 OOV-T uses a floatless carburetor, and bigger intake valves with a new alloy, harder valve seats and valve guides with a higher silicone content for better lubrication in order to handle the higher heat.

Up front Shilling uses a 12-inch spinner instead of a 10-inch standard size, which provides a semi-annular intake to the blower. Such design features turn the engine into a real performer, particularly on a hot day when the density altitude is high.

“All the engine knows is density altitude,” he reminds. “Flying out of Albuquerque on a 110 degree hot summer day, the engine thinks it’s up at 12,000 feet MSL; hence, normally aspirated engines would only put around 50 horses instead of 75. Turbocharged, my Q2 ceiling is around 20,000 feet MSL instead of 16,000, while an unblown engine on a high-DA day would have a service ceiling of only 12,000 to 13,000 feet MSL.”

Turbocharging engines was not new to Shilling with his Q2 - he once owned a Piper Apache and put Rayjay turbochargers on his 0-320 engines, raising the single-engine ceiling from 5200 feet MSL to 11,000 feet MSL.

|

Last year, when Quickie Aircraft President Gene Sheehan won a contract for

10 Q2s from the Shanghai Aircraft Factory, Horvath sent Eric Shilliing to supervise things. Previously, the China National Aero Technology import and Export Corp. had sent mechanics to the Quickie factory at Mojave Airport in California, to learn to build Q2 mockups, but Shilling’s job was to supervise installation of the Revmaster engines and accessories for normally aspirated powerplants.

They already had two Q2s flying,” says Shilling, but their pilots had absolutely no light aircraft time — they’d only flown jets, and the Q2s have an entirely different feel. So I had to check ‘em out.”

Initially, Shilling was confined to a tiny test area, only 3 kilometers square, that he zapped across in seconds. ‘It was strange - the Chinese required that I use radio clearance to start engine, taxi, take off, and on each leg of the pattern. They’d yell at me: ‘Now, don’t taxi too fast!’ All flights were being televised, and the Chinese were being super cautious - after all, they’d built the Q2s and were afraid I might bust ‘em!”

The Chinese at Shanghai finally figured that Shilling, who had fought in their skies during the big war, knew his stuff; so they relaxed their restrictions, and it was all “very pleasant,” Shilling says.

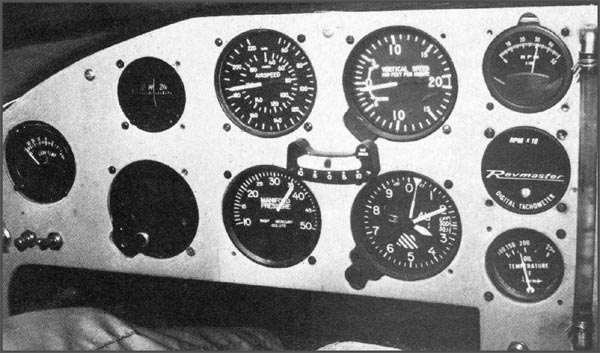

When I flew with him in his Q2 recently, I had my lap full of test equipment, as he was still evaluating the performance of his Turbo 75 Revmaster, so we were considerably over gross at 1175 pounds. Nevertheless, the performance was highly impressive, as may be seen in some snapshots I took of the instrument panel during the flight.

Thus, we were climbing at about 800 fpm to 3000 feet MSL, indicating 122 mph using 32 inches MP and 3000 rpm. Our cruise speed at around 3000 feet MSL was better than 160 mph IAS on 26 inches and 3000 rpm, while the Vmax touched 185 mph AS on 36 inches and 3200 rpm.

All in all, I’d say that turbocharging a small engine makes sense, particularly if you’re flying from high airports or during hot DA summer months, and you still can benefit lower down from smoother engine performance and better fuel economy using the “wet” turbo, as explained earlier.

Gene Sheehan offers complete kits with elongated cowlings to take the Turbo 75 Revmaster, which should give the Q2 equal performance with the 0-200.

Contact: Revmaster Aviation, 7146 Santa Fe Ave. E, Hesperia, Califo. 92345, (619) 244-3074.